This post was originally published in the Peninsula Pulse.

By Myles Dannhausen Sr.

White Cliff Road. Today it’s a name synonymous with wealth and prestige, but last summer a simple garage sale sign reminded me of a time when this road beneath the tall cliffs of Egg Harbor’s Niagara Escarpment was home to the most primitive of Door County living.

I spotted the garage sale sign where White Cliff Road meets Highway 42 at the center of the Village of Egg Harbor. It’s not everyday that you find a garage sale on roads like White Cliff or Cottage Row, so it sparked my curiosity.

When I finally found my target, I entered the driveway of the R.W. Peterson Cottage. Just to the left the long abandoned logging trail I remember from boyhood summers was still visible in the woods. For years that trail was the only way to get to the Peterson cottage.

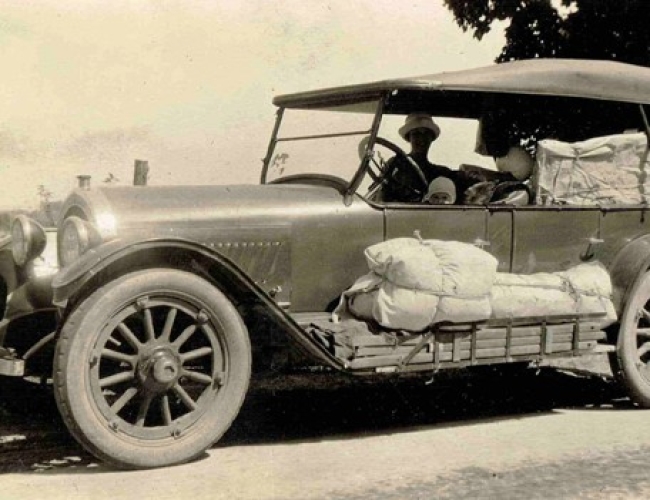

I introduced myself to the few family members gathered outside and I was surprised that they all knew who I was. Soon I found myself inside the cottage with Arleen Peterson, the 89 year-old daughter-in-law of Rudolph W. Peterson, who purchased five acres and 275 feet of shoreline here from Philip LeMere in the early 1920s for a mere $400. On this day the family was selling the last of almost a century of accumulated personal belongings before transferring the property to a new owner.

Today this is as desirable a parcel as one could hope to have on our peninsula, but when I first saw it as a child it was far from it. Remote, untraveled and undeveloped, only someone familiar with these woodlands would notice the dark and mysterious logging trail or risk finding out where it led.

By the 1920s other parts of Egg Harbor were developed. The Alpine Resort opened across the harbor and Horseshoe Bay Farm a few miles south was already a significant agricultural enterprise with its own electricity. North of the Village, however, the area now served by what is now White Cliff Road remained an unexplored wilderness familiar to only a few loggers and hunters. It would remain so for the next 30 years.

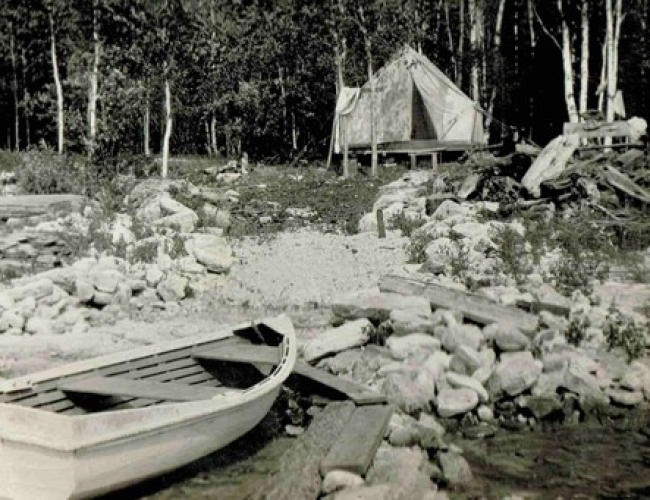

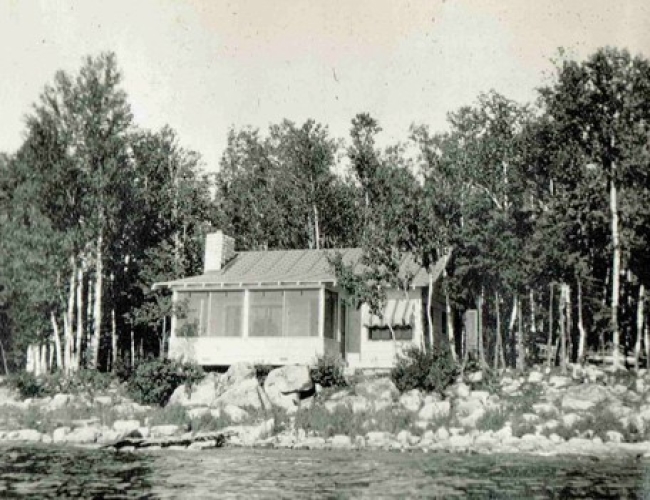

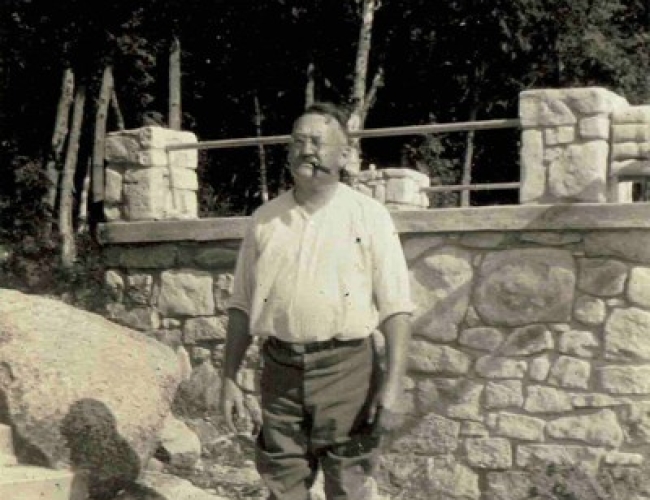

R.W. and his family began what became an annual month-long vacation with only a tent for shelter. Within a few years a small primitive home was created which the family called the “cottage,” followed by a boathouse. Coil springs from old beds were used to reinforce the flat roof of the boathouse which became a deck overlooking the water. The boathouse and beautiful deck still stand today.

Arleen tells us there was no electricity until the 1960s. There was no well until 1972. The well wasn’t needed. The water was so clear, she said, that they simply went to the bay for water. A tastefully decorated outhouse reflects one of the other primitive inconveniences for early White Cliff road residents. For coffee they would boil the water with the grounds and eggshells to clarify the brew. R.W.’s wife Clara was an avid cook and would make cookies, pies, bread and cinnamon rolls on a primitive kerosene stove.

(In 1949 my parents also bought a small cottage about a mile south of the Peterson cottage, and during one of my childhood visits with Clara I also made an Angel Food cake with a Coleman oven that sat on a propane stove. This skill served me well years later in Sierra Leone when I used her lessons to bake bread for my fellow Peace Corps volunteers in a similar stove.)

Over time, Peterson built a simple cottage, pier, and a boathouse. Photo courtesy of Egg Harbor Historical Society.

During the Peterson family’s summer adventures without electricity even food storage was not that much of a problem. Someone would paddle the canoe down to the village pier and get ice housed in a cannery containing ice cut out of the bay during the previous winter. They could also have gotten the ice from Trodahl’s IGA store (later Witallison’s grocery and now Maxwell House, where an ice house still stands), or from VI’s Red Owl, which stood above what is now the Marina.

Limited town government prevailed at the time. They left the Petersons alone except for the requirement that they obtain a permit for burning. The supervisors feared the entire forest could burn if a fire got out of control. Even prohibition didn’t go far down White Cliff road. R.W. kept a box under the house and enjoyed a cool beer from time to time.

The town survived his transgressions.

Arleen, whose father was Rudolph Peterson Jr., first visited the cottage in 1946. There was only one other house on White Cliff Road by that time, a simple cottage above another boathouse.

Soon others emerged, the Whites, Madsons, and my own parents all arrived, families summering in modest cottages on a quiet harbor. R.W. assembled the group at Happy Hour by raising a flag on the boathouse pole about five o’clock each evening.

The three-mile stretch along the shore between the Peterson house and Juddville, split only by an occasional logging trail, remained a pristine wilderness well into the mid-20th century. It is perhaps one of the few places where those of us still living have memories of the peninsula’s most pristine era.

I often hiked the shore to visit Clara before I was even 10 years old; a mile-long trek on my own that few parents would permit today. Along the way I would find skulls of animals larger than deer, odd-shaped trees that some called Indian Marker trees bent to signify the direction of a trail, rock monuments to a distant ice age that stood taller than I was at the time.

Naturally, whoever owned the vast wilderness and swamp would consider its potential for development. At some point a portion of the swamp to the north of the Peterson cottage was dredged and a small inlet was created.

There are still a few hardy souls on the peninsula who are captivated by a frontier experience, but they won’t find it on the now prized and highly regulated shorefront property. I suppose one could come close to what the Peterson’s enjoyed at a campground in Peninsula State Park, but you would be surrounded by swarms of families, gasoline fumes and campfires. Bright as they are, I wonder if the stars we see at night now are ever as bright as those the Petersons saw from their boathouse deck.

Almost from the turn of the last century development has come in the name of progress and profit. At least for most of the 20th century, however, the essential and enduring mystique of the Door Peninsula, with its diverse collective experiences, heritage and environments, remained somewhat intact. With the sale of the Peterson cottage even family recollections of early vacation experiences will fade into obscurity.

The freedom to live close to wilderness for a time, hike through deserted shoreline or forest without fear of invading someone’s private property, or simply to look out over something pristine should not be relegated to the folk history of the peninsula. Perhaps some future visionaries will honor the beauty of our shorelines with the creation of a national park or national seashore somewhere on Lake Michigan and will replicate the Peterson experience allowing others to find what the National Parks Service writes on its website: “The National Parks are for everyone but the special places you find within them will always be your own.”

For the Petersons and a few others, White Cliff Road was for a time one of those special places.

Myles Dannhausen Sr. first came to Egg Harbor with his parents in 1949, and moved to the village from Chicago in 1969. He is the innkeeper of the Bay Point Inn in Egg Harbor, past-president of the Egg Harbor Historical Society, serves on the Egg Harbor Town Board, and is always looking for more stories about the history and people of Egg Harbor.